Client Performance

What Do We Need Client Performance Testing For?

Performance is a tricky topic. Automated performance tests usually run on server side only, that means there is no real browser involved that would render the requested content to output the actual application page the user would see and interact with. While these server side tests are easier on test resources, enable large scale testing and are way easier to automate than a complex UI with JavaScript based logic handling, sometimes you will still need to go one step further:

Server-side performance tests measure the base response time for most essential components of your site but this does not give you an idea what the user perceives. When measuring this you measure client-side performance.

Slow response times for the server are resulting in slow client performance obviously but the other way around is not true. The client has to load additional resources including local resources such as JavaScript, CSS, and fonts. In addition the final page has to be rendered. Rendering is also a multi-step approach due to late changes to the HTML and CSS.

On the user’s side, the important thing is to be able to interact with the application and reach the goal quickly, which means the loading must be fast enough for the user to stay focused and to be able to execute tasks quickly.

Jakob Nielsen offers some advice on perceived performance:

- 0.1 second is about the limit for having a visitor feel as though the system is reacting instantaneously.

- 1.0 second is about the limit for a visitor’s flow of thought to stay uninterrupted, even though the visitor will notice the delay.

- 10 seconds is about the limit for keeping the visitor’s attention focused on the task they want to perform.

Metrics for Perceived Performance

Historically, web performance has been measured with the load event. While this is a well-defined moment in a web page’s life cylce, it does not necessarily correspond to what the user experiences, as this depends on several other factors. So let’s take a closer look at the web page’s life cycle, which can be measured by the following metrics from Performance Timing API:

- domLoading: Got the first bytes and started parsing

- domInteractive: Got all HTML, finished parsing, finished async JS, finished blocking JS, starting deferred JS processing

- domContentLoaded: Deferred JS was executed, DomContentLoaded event fires and triggers event handler for JS

- domComplete: All content has been loaded (aka images and more), DomContentLoaded event was fully processed (attached JS), fire onload event and start processing JS

- loadEventEnd: All JS attached to onload was executed, dust should have settled

As the user judges by visual impression first, newer browsers also expose a Paint Timing API, which offers measurements related to (visually) perceived performance:

- first-paint, which marks the point when the browser starts to render something, the first bit of content on the screen

- first-contentful-paint, which marks the point when the browser renders the first bit of content from the DOM, text, an image, etc.

What Influences Client Performance?

Several components influence how a web page is loaded and rendered.

Initial Load of Content

The first request to an origin to start the entire process is the base for good client performance. When this first request is slow, the rest can only follow but not improve anything. But vice versa, even if the first request is fast, anything after it can still negatively impact the client performance or even render the web page unusable.

CSS

CSS is key to displaying the web page in the design you want. If the CSS is not loaded, nothing is rendered or the browser falls back to the defaults and this is just text formatting.

The CSS has to be applied to the DOM by evaluating every single selector, finding it in the DOM and applying the CSS definitions to the nodes identified.

Fonts

CSS and fonts depend on each other. A font can only be used if it has been loaded and a font will never be loaded, if not used.

Slow font loading can lead to delayed rendering or flashing of content.

JavaScript

Web pages without JavaScript barely exist anymore. A lot of functionality as well as visual styling is done by JavaScript. Additionally, user interaction is driven by the use of the JavaScript event model.

JavaScript has to be loaded, parsed, compiled, and applied. All of these steps are CPU intensive and in combination with a lot of DOM manipulation, it can significantly slow down the display of the page and the time until an interaction with the page is possible.

Images

Images are the heaviest payload most of the time. They shape the overall loading time of the entire page and the bandwidth requirements.

Missing or delayed pictures can lead to content moving while the user already wants to interact with the page.

Network Quality

Depending on the overall network quality, defined by latency and bandwidth, web pages load differently.

But not only the last mile defines the speed but also the distance to certain providers. Therefore a web page served from the US might behave differently when loading from Europe or Asia. Sometimes even being on the West coast in the U.S. and hitting East-coast servers can make a difference.

Network quality can be improved by using CDN providers, but also can lead to negative effects when done incorrectly.

Browser Type

The web is dominated by four main browsers: Internet Explorer, Firefox, Chrome, and Safari. While Safari and Chrome still share some code, IE and Firefox run totally differently. Additionally, IE comes in two flavours, the old Trident engine (IE11 and lower) and the new Edge engine (IE12 and higher).

End User Hardware

Because modern web pages became applications with a load of code that has to be parsed, compiled, and executed as well as with a lot of interactive elements, they can be a CPU burden and therefore run slower on older systems or systems with less memory.

Also, mobile devices, even though they are already full computers, are restricted in CPU and memory, due to the power consumption limitations, and usually run slower or are optimized for battery runtime instead of speed.

Measuring Performance

There are basically two ways to measure the performance of your application: in an automated test environment (for example using XLT), monitoring the above metrics for defined test scenarios, or “out in the wild”, giving your application to real users and letting them evaluate their experience.

While automated performance testing is useful and reasonable to ensure good performance for newly developed features, it is recommended to do both, as automated performance tests are not necessarily reflective of how all users experience your application in their specific environments. The perceived performance can vary a lot depending on the user’s device capabilities and network conditions, and also on the way the user is interacting with your application (which may be different from what you expected when you defined your test scenarios).

Measuring Client Performance with XLT

XLT can be used to measure your application’s client performance in terms of the above metrics, to give you a first insight into your application’s perceived performance. By using a special WebDriver setup, XLT is able to retrieve data from the browser by querying the Performance and Navigation Timing API. This data is then stored alongside the other XLT data and will be available for evaluation in the test report.

To enable performance testing, you need to set up XLT’s web driver (the default setting can be found in default.properties - we recommend you to create a dedicated client performance settings file like test-cp.properties, overwrite the settings there and then use it as the test properties file).

Install ChromeDriver

You might first need to install a suitable web driver, for example the ChromeDriver, which can be found here (pick your preferred version).

Web Driver Settings for XLT

- xlt.webDriver: The WebDriver type to use for XML script test cases and subclasses of AbstractWebDriverTestCase. Possible values are:

- “chrome” - ChromeDriver

- “chrome_clientperformance” - XltChromeDriver (enables client performance timings recording)

- “edge” - EdgeDriver

- “firefox” - FirefoxDriver

- “firefox_clientperformance” - XltFirefoxDriver (enables client performance timings recording)

- “ie” - InternetExplorerDriver

- “opera” - OperaDriver

- “phantomjs” - PhantomJSDriver

- “safari” - SafariDriver

- “xlt” - XltDriver (default)

- xlt.webDriver.window.width/xlt.webDriver.window.height: The desired dimension of the browser window. If not specified, the driver’s defaults will be used.

- xlt.webDriver.reuseDriver: Whether to maintain a single driver instance per thread that will be reused for all tests run from this thread (default: false). This saves the overhead of repeatedly creating fresh driver instances.

- xlt.webDriver.<type>.pathToDriverServer: The path to the driver server executable if the respective driver requires one. If you do not specify a path, the driver server must be in your PATH.

- xlt.webDriver.<type>.pathToBrowser: The path to the browser executable to use. Specify the path in case you don’t want to use the default browser executable, but an alternative version. Supported for “chrome”, “chrome_clientperformance”, “firefox”, “firefox_clientperformance”, and “opera”.

- xlt.webDriver.<type>.browserArgs: The arguments to add to the command line of the browser. Supported for “chrome”, “chrome_clientperformance”, “firefox”, “firefox_clientperformance”, and “opera”.

- xlt.webDriver.<type>.legacyMode: Whether to run “firefox” or “firefox_clientperformance” web drivers in “legacy” mode. In this mode, an add-on is used to drive the browser instead of GeckoDriver. Note that the legacy mode does not work with Firefox 48+. Use Firefox/ESR instead.

- xlt.webDriver.<type>.screenless: Whether to run “firefox_clientperformance” or “chrome_clientperformance” drivers in headless mode (default: false). Requires Xvfb to be installed.

So this would be a valid client performance testing web driver setup (set pathToDriverServer matching your local installation path):

xlt.webDriver = chrome_clientperformance

## ChromeDriver settings

xlt.webDriver.chrome_clientperformance.pathToDriverServer = /usr/bin/chromedriver

xlt.webDriver.chrome_clientperformance.browserArgs =

xlt.webDriver.chrome_clientperformance.screenless = true

## User Agent

xlt.webDriver.chrome_clientperformance.userAgent.desktop = Mozilla/5.0 (X11; Linux x86_64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/60.0.3112.101 Safari/537.36 Xceptance LoadTest

xlt.webDriver.chrome_clientperformance.userAgent.mobile = Mozilla/5.0 (iPhone; CPU iPhone OS 9_1 like Mac OS X) AppleWebKit/601.1.46 (KHTML, like Gecko) Version/9.0 Mobile/13B143 Safari/601.1 Xceptance LoadTest

Client Performance Test Cases in XLT

To enable client performance measurements in XLT, test cases must use the action concept to mark areas for screenshots and time naming. In other words, your UI test cases should extend AbstractWebDriverTestCase or AbstractWebDriverScriptTestCase.

In the latter case (for AbstractWebDriverScriptTestCase) the costructor may be given a Web Driver. If that passed driver is non-null, that is the driver was created by you (you can use the properties for creating this driver, but you do not need to), you are also responsible to quit the driver after the test. However, if the passed driver is null, a default driver will be created and managed internally.

Running the Client Performance Test

To run your XLT client performance test, just make sure you use the right web driver settings and enabled the client performance test cases you wrote, then you can just run a small performance test as usual to measure and sample enough data (keep in mind a much shorter testing window might be sufficient in this case).

Evaluating the Client Performance Test

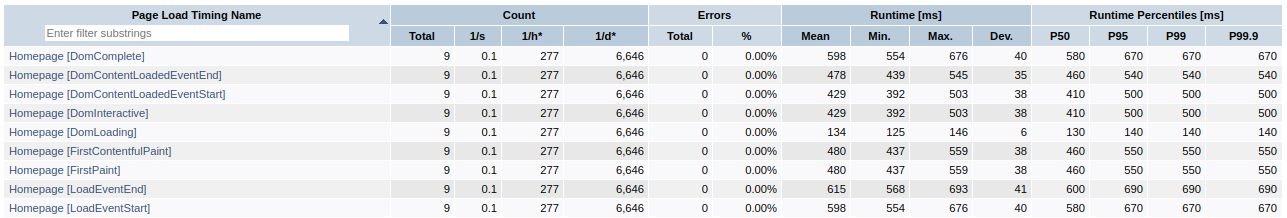

After you executed and finished your client performance load test, you can now create the test report which will contain additional information in the Page Load Timings section. The result will look something like this (example for action named “Homepage”):

Make sure you pay attention to these points:

- Async operations have to be manually identified

- Action time frame has to kept open until these finish

- Late changes of the page are hard to code against

- Prefer

waitForVisibleoverwaitForElement - Don’t use a single number to identify issues or slowness

- Collect enough data to avoid outliers

Your collected data might still not tell the real story in terms of visual impression - of course it takes some experience to evaluate these values, and the measurements can never give you all the insights a live user test could.